At Sirens, attendees examine fantasy and other speculative literature through an intersectional feminist lens—and celebrate the remarkable work of women and nonbinary people in this space. And each year, Sirens attendees present dozens of hours of programming related to gender and fantasy literature. Those presenters include readers, authors, scholars, librarians, educators, and publishing professionals—and the range of perspectives they offer and topics they address are equally broad, from reader-driven literary analyses to academic research, classroom lesson plans to craft workshops.

This year, Sirens is offering an essay series to both showcase the brilliance of our community and give those considering attending a look at the sorts of topics, perspectives, and work that they are likely to encounter at Sirens. These essays may be adaptations from previous Sirens presentations, the foundation for future Sirens presentations, or something else altogether. We invite you to take a few moments to read these works—and perhaps engage with gender and fantasy literature in a way you haven’t before.

Today, we welcome an essay from Casey Blair!

Women Are Already Powerful:

The Problem of Privileging Masculine Modes of Power in Fantasy

By Casey Blair

The fantasy genre continues to change and grow in response to how we—the writers, book purveyors, reviewers, educators, publishing professionals, and most importantly of all, the readers—push it. When we challenge standards and accepted limitations of what we want to read and what sells, we shift the landscape of stories available to us. We have the power to effect change, when enough of us across intersections care enough to exert that pressure. We see that power in effect—that it exists, and that we have a whole lot more work to do—in the way the publishing industry is putting out and celebrating more fantasy stories by and about marginalized people, and in particular, more stories about powerful women.

Women lead revolutions, women wield unprecedented magical powers, and women punch gods and monsters. Women helm stories of action and adventure, the kinds of stories boys have never had to search for to see themselves in. Especially in the young adult space, we are swimming in stories of women starring in fantasy worlds, and that is a victory worth celebrating.

But what I don’t see as much of, and I wish I saw more, are stories that center women where masculine modes of power aren’t upheld as the pinnacle, as the most important, as the only power worth aspiring to. Women should absolutely star in stories of fantasy combat and commanding revolutions. As Kameron Hurley has discussed, women, in all ages of history and all around the world, have always fought—and we deserve to see that in our fantasy. But women have exercised lots of other forms of power, too, and they’ve fought in many different ways, and we are still all too often erasing those ways from our stories, as well as our conversations about and acclaim for why all those ways matter.

Publishing won’t put out those stories in greater percentages or put more marketing dollars behind them if we don’t demand it of them, so I want to dive into why these stories that uplift feminine-coded forms of power are so important, and what it means that they’re comparatively rare. Which is not to say they don’t exist at all, or that we should slow down on writing stories about women stabbing the patriarchy with swords especially now that people of color and queer folk are beginning to be centered in more of them. Just that feminine-coded power, and its problematic erasure or devaluation, gets a lot less attention or celebration even though it can be just as inspiring and revolutionary.

I’m going to be talking about “coding feminine” or “masculine” as shorthand, so let me define that briefly, if broadly: These are the acts, the work, and the presentations we, in our western social framework, traditionally and stereotypically associate with the male or female gender. Big muscles and taking up space are coded masculine; daintiness and humility are coded feminine. Solving problems by punching is coded masculine; with teamwork, feminine.

So a fantasy that gives us an outgoing and belligerent heroine who loves sports, excels at punching, doesn’t care about dresses, and refuses to work with people—this is coding her power as masculine. And that’s not a bad thing! Women characters wielding masculine-coded power challenge the gender stereotypes that only men are able to succeed with that kind of power, the swords and the aggression and the alone-ness. Women absolutely can too, and I love these stories. The problem is with trends, historical and current.

For decades, we’ve read troves of fantasy focusing on men wielding masculine-coded power and generally not even noticing feminine-coded power exists, or if it does devaluing it or even making it evil. And in our current era, while that kind of fantasy doesn’t eclipse all the other fantastic work out there, by and large most fantasy stories starring women cast them in roles wielding masculine-coded power. These women are dueling to the death. They’re breaking communities with revolutions. They’re throwing away their dresses and donning pants. And while none of those are problems in and of themselves, there is a problem when over and over feminine modes of power are consistently abandoned, trashed, buried, and erased.

There is a problem when the only, or even the primary, way we can imagine women in stories focusing on action and adventure is to make them reject feminine modes of power. There’s a problem when the vast majority of women our stories present as heroes, as powerful in their own right, are coded masculine. There is a problem when you have a whole lot of women in your story, and all the Aryas, the warrior women, are narratively favored, where the Sansas, who try to follow traditional paths for women, have the most horrifying storylines. Not all the heroes of any gender should have to wield masculine-coded power to be at the center of a story—whether or not the story focuses on action and adventure.

The problem, to be clear, is that we’re tacitly upholding toxic masculinity by not challenging the underlying assumption that women who don’t behave in traditionally masculine ways are not just as powerful and as capable and deserving of adventures, in our stories and in our reality. When the dominant trend in our stories is to privilege masculine modes of power over feminine, and those are the stories we dominantly celebrate, that’s the message we send, absorb, and perpetuate.

I don’t just want to see women in my fantasy books who decide they should be able to wear pants, too, and work to make that happen. I want to see women and people of all genders who wear dresses proudly in a pants-dominated world and are treated with just as much respect without working multiple times as hard for it.

Or, to put it another way: I don’t want women to have to reject dresses to be taken as seriously as the people who wear pants. Women shouldn’t have to reject femininity to be powerful, and that is just as important in our fantasy as it is in our reality.

Women are already powerful.

***

Stories are both mirror and window. They help us figure out who we are and who we can be. They help us cope with our reality and imagine other ways of being.

So when we see that our stories dominantly privilege masculine-coded modes of power—of physical strength, noncooperation, aggression—it matters. The prevalence of this trend sends a clear and awful message that traditionally feminine modes of power aren’t, in fact, worthwhile. That women who want to wear dresses and talk problems out instead of stabbing them in their fronts are weak, and passive, and can’t go on adventures. I reject wholeheartedly the premise that to have power in our stories, which reflect the truth of our reality and offer possible escapes, we have to reject femininity, too.

We do ourselves a disservice upholding traditionally masculine roles as modes of power for women without also modeling femininity as strength worth aspiring to—by which I mean not inherently evil—by not also modeling that men don’t have to be brilliant warriors and ruthless princes to be heroes or to be desirable as heroes. We can’t unravel toxic masculinity if we don’t value other kinds of power for all genders, and worse, right now our stories are helping uphold it by dominantly privileging traditionally masculine modes of power for everyone.

And we can’t value other kinds of power when we erase and devalue them from our stories.

***

What other kinds of power do I mean? What does this look like? Happily, examples do exist in fantasy, even if they’re not the majority, so let’s look at some specifics.

Nahoko Uehashi’s Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit subverts gender role expectations across the board. Our protagonist Balsa is a professional fighter not because she has to be, but because she chooses to be. She’s not the only female character, either: The Second Empress uses her political power, which functions differently than the Emperor’s, to thwart him and save her son; for contrast the oldest and most powerful shaman is a woman who is explicitly called ugly, making it clear her power is not connected to beauty or any kind of feminine wiles.

On another side, our primary healer character, who may or may not be a love interest, is a man, not a woman. And the character who is forced to give birth to a magical egg is a prince, not a princess. Balsa is our protagonist, but in this book she’s also just the bodyguard: The prince must do the work of bearing the egg, and Balsa couldn’t protect him without the work of the healer. With this framing, Uehashi makes it clear both that avenues for different kinds of women to exercise power exist and, importantly, that the traditionally coded feminine roles are valuable work, while simultaneously centering a woman.

So this is the first way to successfully navigate giving us satisfying stories of action and adventure while avoiding the problem of privileging masculine modes of power for women in fantasy: Center the women with masculine-coded power but still uplift feminine-coded power by granting it to leading male characters and making it integral to the resolution of the plot. Feminine-coded power doesn’t have to be the sole province of women, nor should it be, lest it function as a way to pressure women into exerting only feminine power, which is its own trap. But including feminine-coded power as a desirable mode for other genders is one way to keep from restricting valuation of that power.

Stories can apply this kind of reversal—subverting gender expectations for centered women while also valuing feminine-coded power—in a lot of ways. In Robyn Bennis’s The Guns Above, our heroine is an airship captain who is very good at soldiering, while the male dandy assigned to spy on her is the one who is sensitive to people’s emotional needs. The story requires both their skillsets to get them out of trouble. In C.L. Polk’s Witchmark, our gay male hero is a healer, and it’s his sister, mindlessly following in the steps of her father’s masculine-coded ruthless heartlessness, that is the villain. In this case, victory requires a complete rejection of the dominant power system that subjugates others.

In Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lightning, our protagonist Maggie Hoskie is skilled and supernaturally talented at killing, while Kai Arviso is a medicine man still coming into his full power who needs Maggie to protect him—and he is also a love interest who is not preternaturally gifted at combat, and (BRIEF SPOILER) the one Maggie chooses (END SPOILER). Trail of Lightning is also in many ways a refutation of this kind of gender coding: others use the fact that Maggie Hoskie is a woman in possession of killing powers at all to make her out to be a monster, and unnatural, which she at turns embraces or rejects.

In Laini Taylor’s Dreamdark series, she sets up a similar dynamic in Magpie Windwitch, who is a champion because she’s the only faerie who can weave the tapestry of the world, but a hero not because of what she can do with magic or in battle, but because she’s committed to acting. And also in Talon Rathersting, who learns how to knit magic—so he can fly, and so he can keep his friend from being lost. Laini Taylor makes fiber arts and keeping people together, two skills traditionally associated with women, valuable in the world at large as well as for men specifically.

In these stories, we get to have it all: action and adventure without privileging toxic masculinity. Tamora Pierce’s Circle of Magic series shows us another way to do this with a group of four main characters: Sandry, a noblewoman whose magic is tied not just to fiber arts, but specifically to the perceived lower-class craft of weaving which includes weaving people together; Daja, who hails from a merchant clan—which is not coded as a masculine endeavor—and whose powers are tied to blacksmithing, which is; Tris, whose magic is fantastically destructive—which the narrative paints as problematic, not desirable—and who gets to be an explicitly angry, emotional woman without that making her less worthy or powerful; and Briar, our one boy, whose magic is tied to plants and gardening, which we traditionally associate with women. Every protagonist, taken individually and as part of a collective, challenges our understanding of gender-coded modes of power.

***

All these examples so far largely feature gender flipping, so before I go any further we have to take a minute to talk about matriarchies in fantasy, when it’s not just individual characters challenging gender roles but the entire fantasy society. Some fantasy matriarchies do a simple, blunt gender role swapping, having women exercise masculine-coded power and devaluing or subjugating feminine-coded power in men. Others take a more nuanced approach and bake the analysis into text with more subtlety.

We can talk about the outrageously popular middle grade Wings of Fire series by Tui Sutherland, which follows a group of dragonets who think they’ve been chosen to save the world, and each book of the initial quintet focuses on one of them. Sometimes the female dragons are the strongest or best fighters, and sometimes they aren’t, but in this matriarchal world they are always assumed to be the natural leaders. The series evaluates the flaws of masculine-coded antagonistic, heartless, and physical strength-based leadership modes on the page, and ultimately, amidst all the combat and bloodshed and assumptions of their necessity, it’s the tiny female dragonet who wants everyone to work together who is able to figure out how to end the decades-long dragon war.

We can talk about In Other Lands by Sarah Rees Brennan and its misandrist elves, how the narrative hilariously and blatantly critiques traditional patriarchal arguments by flipping them on their head. We can also talk about how our bisexual male hero navigates through and around his narrow-sighted, war-focused comrades with a combination of blithely ignoring rules, which is traditionally a men-only prerogative, but also a commitment to diplomacy, nonviolence, and bringing people together, which is associated with women.

We can also talk about Martha Wells’s Raksura series and its, as the author describes them on John Scalzi’s “The Big Idea,” “matriarchal bisexual polyamorous flying shapeshifting lizard-lion-bee people.” Her world-building is significantly more complex than a simple gender flip, problematizing and elevating different social roles, how they interact with gender coding, and what those consequences look like on both a societal and narrative level.

***

“This is all well and good,” you may be thinking, “but these are mostly women in masculine modes of power even if those modes aren’t privileged above feminine. Don’t you have examples of women centered and exercising valued feminine-coded power?” I do indeed, but not as many as I want.

Gender flipping and subversion is only one way to navigate the problem of privileging masculine modes of power. Some of the authors I cited above in fact operate in multiple modes: Tamora Pierce, for instance, gives us Alanna, who is not only a warrior but also a healer, and the latter is just as critical to her character even if people tend to focus on the swords. Nahoko Uehashi’s The Beast Player gives us Elin, who wants nothing more than to care for magical creatures and stay out of world politics and battles. Authors can successfully center women exercising feminine-coded power in fantasy adventures in so many ways, it’s infuriating to me how few I can point to and how little I hear this highlighted.

So what does this look like in practice? Let’s start with Rowenna Miller’s Torn, which values feminine-coded work from top to bottom. In this book, our heroine is a professional seamstress who stitches charms into dresses. It’s protective work and homemaking in fiber arts in particular, disciplines traditionally associated with women. Moreover, she’s also a business owner and pillar in her community, sharing her knowledge and uplifting other women in feminine-coded skills when she can. When men discover just how powerful her ability can be, they try to control her and twist her ability, and she masters her power to subvert their violent goals without having to follow their toxic paths to power.

The thread of community-building leads me to modes of leadership that code feminine rather than masculine, based less on dominance than on coming together, and for this reason two books I will tell everyone to read forever are Bitterblue by Kristin Cashore and The Goblin Emperor by Sarah Monette writing as Katherine Addison. I group them together in this context because both are fundamentally about whether it is possible—and how—to rule, to exercise power inherited from a deeply toxic foundation and history, with compassion. In Bitterblue, our heroine learns how to bring people together to begin healing not by ignoring the past or forcing people to expose their pain, but by creating a space where it is safe to do so. The Goblin Emperor codes Maia’s power feminine, is clear that he has been and is punished for it, and nevertheless, little by little, inexorably, he learns how to use his power to build bridges, literally and figuratively. He learns how to accept the institutionalized and personalized traumas the people he wants to lift up are starting from, and he surrounds himself with women who are likewise committed to lifting each other up. Both books analyze the failures of privileging masculine modes of power and actively work to uplift feminine modes.

Mirage by Somaiya Daud, a Moroccan-inspired space fantasy, not only centers compassion, it includes an incredible variety of women in positions of power: princesses and fighters, old and young, from the ruling culture and from the oppressed. That variety isn’t limited to living women, either: Even in the world-building, revered cultural heroes are women, and they are both warriors and poets, providing acknowledged, valued paths for women to wield different kinds of power. In this book, our heroine Amani doesn’t lead a revolution. Her true power is borne out of her ability to understand and communicate with different groups of people, to weave the foundations of peace when no one else is even looking for it. And she still gets action, adventure, and romance out of it.

Listening, sharing, adapting, negotiating, and leveraging networks—all of these traditionally feminine-coded skills are incredibly powerful. The Inda series by Sherwood Smith, which is at once epic fantasy, military fantasy, and fantasy of manners, is a masterful example of the many different kinds of power women can wield, or are forced to wield, when dealing with patriarchal frameworks. There are women for whom beauty is a curse or a weapon or both; there are women who fight in quiet ways, smiling ways, or stabbing ways. There are women who take the lessons of power from one culture and then have to apply them or learn new ways in different cultures. There are women who form networks to work together to survive patriarchal systems as we simultaneously watch those systems, and the men who internalize their ideals, rot from the inside.

Tasha Suri’s Empire of Sand is one of my latest favorite examples of the different kinds of feminine-coded power women can wield in fantasy, one reason being she gives us multiple modes of feminine-coded power exercised at the same time, because why choose? In this book with its setting inspired by Mughal India, Tasha Suri gives us a window into what power looks like for women at court: those on the top, and those distinctly not, and how it functions differently within the sphere of other women and also more broadly—we see the power of controlling who sees women’s bodies, and we see women both lifted up and undercut by other women. We also see women’s power exercised outside the court: We see women leading nomadic communities, managing logistics, information, strategy, and social bonds. We see women in dangerous magical cults, as the enforcers and as the ones who create community bonds there, too.

More than that, we see our heroine Mehr with her complicated heritage navigate through these different spheres, finding her strength when people are always trying to control her, which is a narrative that rings deeply true to the experience of being a woman in a patriarchal world: survival and agency in the face of oppression. Mehr’s magical power, and that of her love interest, is borne out of dance, which is coded feminine—and it is in learning to exercise her power as a woman inside and outside these systems that she succeeds: she learns how to embrace her power but refuses to burn the world with it.

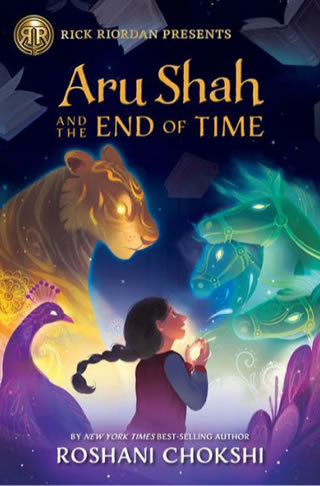

And last but the opposite of least is Roshani Chokshi’s The Gilded Wolves, firstly because one of the best ways to accomplish everything I’m talking about here is just by having multiple important characters, and specifically multiple important women characters. Going back to gender subversion, even just among our group of main characters, there are boys who want nothing to do with violence and boys whose talents lie in communicating with others, which are feminine coded skills, and one boy who wants to rise to the top no matter what in traditionally masculine-coded fashion, which the narrative paints as tragic and flawed. Then there’s Zofia, an autistic Jewish girl who has difficulty understanding people, but she’s brilliant at mathematics, engineering, and explosions. And what more can you want in a heroine, right?

The answer to that is Laila, who doesn’t subvert gender roles at all except in the expectation of their comparative weakness, because she embraces her feminine coding powerfully. Her power is so fundamentally, fantastically coded feminine. Laila may not be human but understands people perfectly: her emotional intelligence is practically psychic, and she always knows what someone needs, whether it’s words or cake. She’s not just a genius at emotional management, but at baking, dancing, and consciously wielding her beauty and sensuality. Because that’s the critical second part of how The Gilded Wolves succeeds in navigating the problem of privileging masculine modes of power: it’s not just a matter of having multiple kinds of men and women; it’s how the narrative depicts that power. Laila, with her strong coding as feminine, is undeniably, unabashedly powerful, not only to the reader but within the narrative of the story, and the fact of her fictional existence is inspiring.

Domestic arts and crafts, logistical organization, physical appearance, healing, protection, compassion, community-building. Traditionally feminine-coded modes of power are power. And I think it’s worth pointing out, too, that every single book I’ve cited here features action and adventure while uplifting feminine-coded forms of power. Every. Single. One.

Power, adventure, and heroism for women do not have to come at the cost of feminine coding, because they are not mutually exclusive, and we need our stories to stop perpetuating that erasure and devaluation.

***

So again, I’m not saying that books that center feminine-coded power as worthy don’t exist; they clearly do. Nor am I saying that now that we have a lot of stories about women—and, let’s be clear, a lot of stories particularly about cisgendered, heterosexual white women—exercising masculine-coded modes of power that we don’t need or want more of them.

What I want, and what we need and deserve as a society full of women who have always exercised a wide variety of power, is a fuller variety of stories and appreciation of that diversity. We can read, value, and push for more than one kind of story at the same time. I don’t just want to be able to point these stories out as exceptions to the trend, for the work they’re doing to be so rare or rarely noticed that it merits highlighting. Because I don’t just want stories that say women can wield a sword as well as a man can; I want stories that say also that sword-wielding may not be the best way to resolve our problems. Women can lead just as powerfully in the ways they always have—and that includes fighting the way men are usually credited with, but it also includes ways we erase. We’ll never value feminine power if we don’t write it into our stories as valuable, and valuable to everyone.

The first part of that task is on all of us: It’s being aware of the messages we’re sending, whether we’re creating stories or promoting them, what we’re absorbing as readers and what we’re choosing to read, what those implications mean when we follow the logic all the way down, and what it means for these stories to be the exception rather than the norm in mainstream fantasy. I hope if nothing else this essay provides some tools to think about the ways we tend to privilege masculine-coded power in fantasy going forward and the many incredible other ways we can set up our stories, and demand from our stories, if we choose to.

Because it’s not much of a choice to wear pants or wield a sword if the alternative is passivity, victimhood, villainy, or the inability to be the star a fantasy adventure centers around. I want more worlds that understand that isn’t the only option. I want more stories that are able to see other ways, and value them, and model them for all of us—not just as a mirror to hold up to nature, but also as a door, to escape into what we all can be. And I hope that’s a direction where we can encourage the fantasy genre to grow.

Casey Blair is an indie bookseller who writes speculative fiction novels for adults and teens, and her weekly serial fantasy novel Tea Princess Chronicles is available online for free. She is a graduate of Vassar College and of the Viable Paradise residential science fiction and fantasy writing workshop. After teaching English in rural Japan for two years, she relocated to the Seattle area. She is prone to spontaneous dancing, exploring ancient cities around the world, wandering and adventuring through forests, spoiling cats terribly, and drinking inordinate amounts of tea late into the night.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter